Prior to the financial crisis, one of the larger concerns facing us all was the impact of our economic development upon the planet. The conversation was discussed in a way that held that there was a trade off between economic growth and prosperity on the one hand, and environmental degradation and resource depletion on the other. These links were well made.

For over 200 years, prosperity had risen. If we compare the average living standard prior to the industrial revolution to the average living standard today, then, at least in the UK, even after the great recession, we are better off today by an order of magnitude. We live longer and healthier lives, with a far greater level of material consumption than our forebears could even dream of. This improvement in our lot is the result of 200 years of economic growth, fuelled by the many technological and organisational developments during that period. Indeed, in our own times, the history of the last 40 years is one of literally hundreds of millions of people moving out of poverty in China and India as a result of economic growth in those countries. To date, economic growth is the vehicle by which prosperity has been delivered.

It is also the case that economic growth has been achieved at the cost of environmental degradation and resource depletion. One only has to think of modern levels of air pollution, acid rain, and the changing climate to take the point that 200 years of economic growth across the globe has had a detrimental impact upon the environment. Some may argue that environmental degradation is a price worth paying for material prosperity, but fewer people nowadays adhere to that cause. Economic growth has also led to the depletion of a number of key resources. Not only the obvious ones such as energy resources, but also implicit ones such as our ability to convert carbon dioxide into breathable oxygen on a planetary level. In that respect, we are poisoning the air we breathe, the water we drink, and the food we eat.

We have allowed this to happen because the cost of the material goods and services that we consume contains a significant external cost that isn’t taken into account in the market price. In the absence of a mechanism to bring the social cost - the private cost we pay, along with the external costs which we don’t pay – into line with the market cost, then the process will continue unabated. Increased prosperity generated by economic growth, at a cost of increased environmental degradation and resource depletion, is a process that can run until we hit the resource limit of a finite planet or until we make our planet unlivable. We do not hazard a guess at which will be the sooner.

For some years, a number of people and organisations, concerned at how this process could run unchecked, have attempted to draw our attention to the problem. Tim Jackson’s 2009 book “Prosperity without Growth: Economics for a Finite Planet” provides a good example of the work in this genre [1]. By and large this constituency has been listened to politely, but no effective action has been taken to address the issue. The great recession has provided us with some interesting data on why that might be and what the problems of addressing the issue might look like.

In 2008-09, in many advanced economies ceased to grow. Many shrank. Since the onset of the great recession, the policy response is to return to business as usual in terms of growth. There has been moderate success in achieving this over the past eight years in the US and the UK. There has been very little success to date in Europe and Japan. As parts of the global economy starts to climb out of stagnation, perhaps it might be time to take stock.

The recession has been kinder to the plant. Resource depletion has abated as falling levels of demand softens the markets for resources, the most dramatic example of which is the fall in the price of oil. With lower levels of economic activity the degradation of the planet will have slowed. To that extent the great recession has made the global economy more viable for the environment. We have seen, however, less growth and less prosperity. In the advanced nations poverty and inequality has increased, and it is the desire to alleviate that poverty and inequality that underwrites the desire for higher growth. We seem to be in a vicious circle that has no apparent resolution. Perhaps we are looking at the wrong issue?

For over 200 years, prosperity had risen. If we compare the average living standard prior to the industrial revolution to the average living standard today, then, at least in the UK, even after the great recession, we are better off today by an order of magnitude. We live longer and healthier lives, with a far greater level of material consumption than our forebears could even dream of. This improvement in our lot is the result of 200 years of economic growth, fuelled by the many technological and organisational developments during that period. Indeed, in our own times, the history of the last 40 years is one of literally hundreds of millions of people moving out of poverty in China and India as a result of economic growth in those countries. To date, economic growth is the vehicle by which prosperity has been delivered.

It is also the case that economic growth has been achieved at the cost of environmental degradation and resource depletion. One only has to think of modern levels of air pollution, acid rain, and the changing climate to take the point that 200 years of economic growth across the globe has had a detrimental impact upon the environment. Some may argue that environmental degradation is a price worth paying for material prosperity, but fewer people nowadays adhere to that cause. Economic growth has also led to the depletion of a number of key resources. Not only the obvious ones such as energy resources, but also implicit ones such as our ability to convert carbon dioxide into breathable oxygen on a planetary level. In that respect, we are poisoning the air we breathe, the water we drink, and the food we eat.

We have allowed this to happen because the cost of the material goods and services that we consume contains a significant external cost that isn’t taken into account in the market price. In the absence of a mechanism to bring the social cost - the private cost we pay, along with the external costs which we don’t pay – into line with the market cost, then the process will continue unabated. Increased prosperity generated by economic growth, at a cost of increased environmental degradation and resource depletion, is a process that can run until we hit the resource limit of a finite planet or until we make our planet unlivable. We do not hazard a guess at which will be the sooner.

For some years, a number of people and organisations, concerned at how this process could run unchecked, have attempted to draw our attention to the problem. Tim Jackson’s 2009 book “Prosperity without Growth: Economics for a Finite Planet” provides a good example of the work in this genre [1]. By and large this constituency has been listened to politely, but no effective action has been taken to address the issue. The great recession has provided us with some interesting data on why that might be and what the problems of addressing the issue might look like.

In 2008-09, in many advanced economies ceased to grow. Many shrank. Since the onset of the great recession, the policy response is to return to business as usual in terms of growth. There has been moderate success in achieving this over the past eight years in the US and the UK. There has been very little success to date in Europe and Japan. As parts of the global economy starts to climb out of stagnation, perhaps it might be time to take stock.

The recession has been kinder to the plant. Resource depletion has abated as falling levels of demand softens the markets for resources, the most dramatic example of which is the fall in the price of oil. With lower levels of economic activity the degradation of the planet will have slowed. To that extent the great recession has made the global economy more viable for the environment. We have seen, however, less growth and less prosperity. In the advanced nations poverty and inequality has increased, and it is the desire to alleviate that poverty and inequality that underwrites the desire for higher growth. We seem to be in a vicious circle that has no apparent resolution. Perhaps we are looking at the wrong issue?

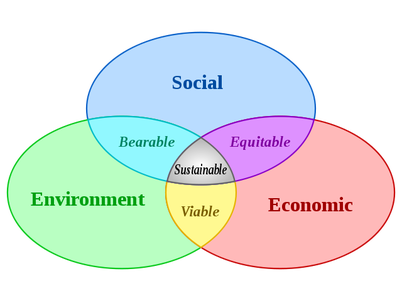

The Brundtland Model

The Brundtland Model A different way of looking at the issue has been provided by the Brundtland Commission [2]. This constructed a model, as described in the accompanying diagram, consisting of three elements. It suggests that a long term sustainable solution to our predicament needs to balance the interests of the economy, the environment, and society. The great recession has eased the tension between the economy and the environment, but at the cost of making the tension between the economy and society that much greater. To respond to this by returning to ‘business as usual’ might ease the tension between the economy and society, but at the cost of increasing the tension between the economy and the environment.

The apparent problem requires not only policies to address the question of environmental degradation and resource depletion, but also to address the question of poverty and inequality at the global level, if we are to reach an outcome that is lasting. If a solution emerges which people feel is unfair, however ‘unfairness’ may be defined, then there will always be an incentive to move towards a fairer solution through greater economic growth, leaving us back where we started. Previous attempts to resolve the consequences of economic growth, such as climate change, have stalled precisely on the questions of equity. The benefits of climate resolution are shared equally, but the costs aren’t. Until they are, then those nations suffering as a result of climate mitigation, which are mainly the emerging economies, have very little incentive to reach a resolution to the problems of environmental degradation and resource depletion.

Can we have prosperity without growth? It could be possible if we were to develop a feeling of ‘enoughness’ amongst those of us in the rich world, and a willingness to share our surpluses with those who do not have enough in the emerging world [3]. However, the evidence suggests that this is too utopian for our current frame of mind, which means that growth will be the key to prosperity for the foreseeable future, and that environmental degradation and resource depletion are something that we will have to learn to live with as we move into the future.

Stephen Aguilar-Millan

© The European Futures Observatory 2015

References:

[1] “Prosperity without Growth: Economics for a Finite Planet.” by Tim Jackson (Earthscan 2009). For my review of the book on Goodreads, see: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/10805219-prosperity-without-growth

[2] For more information on the Commission, see: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brundtland_Commission.

[3] See: “How much is enough?” by Robert & Edward Skidelsky (Allen Lane 2012). For my review of the book on Goodreads, see: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/15707945-how-much-is-enough.

The apparent problem requires not only policies to address the question of environmental degradation and resource depletion, but also to address the question of poverty and inequality at the global level, if we are to reach an outcome that is lasting. If a solution emerges which people feel is unfair, however ‘unfairness’ may be defined, then there will always be an incentive to move towards a fairer solution through greater economic growth, leaving us back where we started. Previous attempts to resolve the consequences of economic growth, such as climate change, have stalled precisely on the questions of equity. The benefits of climate resolution are shared equally, but the costs aren’t. Until they are, then those nations suffering as a result of climate mitigation, which are mainly the emerging economies, have very little incentive to reach a resolution to the problems of environmental degradation and resource depletion.

Can we have prosperity without growth? It could be possible if we were to develop a feeling of ‘enoughness’ amongst those of us in the rich world, and a willingness to share our surpluses with those who do not have enough in the emerging world [3]. However, the evidence suggests that this is too utopian for our current frame of mind, which means that growth will be the key to prosperity for the foreseeable future, and that environmental degradation and resource depletion are something that we will have to learn to live with as we move into the future.

Stephen Aguilar-Millan

© The European Futures Observatory 2015

References:

[1] “Prosperity without Growth: Economics for a Finite Planet.” by Tim Jackson (Earthscan 2009). For my review of the book on Goodreads, see: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/10805219-prosperity-without-growth

[2] For more information on the Commission, see: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brundtland_Commission.

[3] See: “How much is enough?” by Robert & Edward Skidelsky (Allen Lane 2012). For my review of the book on Goodreads, see: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/15707945-how-much-is-enough.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed